by Gabriele Bonafede

Until the first quarter of 2021, most forecasting institutions had been predicting that UK economy would start recovering at the beginning of 2021. These predictions have been already proved wrong. For the first quarter of 2021 there has been an additional contraction for UK GDP (-1.6%, which is a -6.1% at annual rate).

This is adding to the horrific year-to-year plunge of -9.9% occurred in 2020. Bank of England (BoE) and other forecasting institutions have therefore postponed and increased the recovery schedule and the amplitude of growth for UK economy.

Again, they risk being wrong as we enter the second half of 2021. In fact, forecasts about inflation, UK supply-chain’s resilience and labour shortages have already been proved wrong too. Inflation in UK is currently running, in official data, at 2.3-2.4% and increasing – which is much higher than previously forecasted.

A few forecasting institutions (such as NIESR, National Institute for Economic and Social Research) have already put the figure at 3% for mid-2021. We can expect updates of rising inflation in coming weeks.

Supply chain, shortages and inflation: empty shelves

Empty shelves in UK supermarkets are a strong signal of goods and labour shortages, especially in the production and distribution sectors. The main reason for all these failures in forecasting macroeconomic indicators is an over optimistic view of Brexit’s impact.

The real impact of Brexit is being underplayed by many forecasters and media, particularly when they have close links with UK government. For instance, the UK government has been trying to find a scapegoat for empty shelves in supermarkets, i.e. the “pingdemic”.

The real reason for empty shelves is a shortage in labour supply for distribution and additional shortages in domestic production (both goods and services) coupled with lower levels of imported goods from the EU.

In addition, the macroeconomic outlook should take into account financial markets. Here, London’s financial markets do not show signs of recovery with respect to the 2021 spring plunge. The FTSE 100 is still below pre-pandemic levels: one of the few major indices still failing a full recovery from a dive of epochal proportions. This is another strong signal of sluggish economic recovery, often neglected.

Supply chain, shortages and inflation: a self-fuelling Brexit disaster

The general macroeconomic picture shows that Brexit is having the effect of a “cap” on the UK’s economy. The UK might still have benefits coming from an “early” exit from pandemic thanks to a massive and rapid vaccination campaign.

Yet, these benefits are being capped by structural limits stemming from Brexit. In other words, Brexit might be triggering a massive macroeconomic “stagflation” trap for UK. That is, a number of self-fuelling economic events bound to trickle-down the entire supply side of the economy and, eventually, the entire UK economy.

A clear example is the effects of a disrupted supply-chain on inflation. In fact, Brexit is producing shortages of labour supply and domestic goods & services now impossible to produce without necessary workers. In addition, easy import of goods from EU is not an option anymore without fuelling inflation too.

All of that, in turn, is producing subsequent rounds of both lower supply-levels and tight labour markets, pressuring salaries upward without a parallel increase in productivity. For instance, the haulage industry of UK has now a chronic driver shortage worsened by Brexit. This is just one of the many examples of this perverse mechanism.

Risk of a spiralling inflation with little or no growth

That is because workers cannot come anymore from other EU countries as easily as before Brexit. As a result, production in goods and services is getting “capped” while supply chains get jammed. Businesses have to increase salaries to hire missing workers, without any increase in productivity – or stop production as it is happening for some UK agriculture and service sectors.

With fewer goods and workers available, prices and salaries get higher. In turn, higher salaries without higher productivity make prices higher still. The mechanism can get out of hand very easily and lead to a spiralling inflation without a real GDP increase.

These factors, without any reasonable policy from the UK government other than hiding the truth, are destined to produce subsequent rounds of higher prices without any increase in productivity.

Since these factors are not temporary, inflation is probably going to persist. In other words, the inflation being experienced does not look to be temporary. It looks permanent in its structure, due to Brexit. And it can get spiralling unless BoE or UK government start acting in the right moment and the right way. Something which is hardly granted.

Trusting econometric models is good, not trusting is better

I am not supporting the above considerations with fancy econometric models used by large forecasting institutions. True, complex econometric models are the best way to forecast in any case.

The fact is, even the IMF in January 2020 failed to forecast the extent of the UK GDP contraction of 2020. And it failed again in April 2020. In January 2020, when the pandemic was already infecting China at amazing rates, IMF predicted a GDP increase for UK of 1.5%. In April 2020, when Covid-19 and lockdowns were ravaging the world, the IMF updated the figure to an optimistic -6.1% for the UK. Eventually, the UK economy fell by a “staggering” -9.9%…

Why?

That is because some econometric models – understandably – do not always utilise up to date and day-to-day (or monthly) observations of macroeconomic data coupled with specific risks about external events (such as pandemics or particularly silly governments). They just follow on events, which results in delays in providing a reliable forecast.

This is especially the case when hidden risks (or politically-sensitive risks) are unobserved by standardized or sophisticated models.

In addition, some econometric models might not be equipped with mechanisms to include more specific political risks and other “external shocks”, for example issues such as Scottish independence, Northern Ireland sectarian fights or dodgy PMs…

“Emilia Perez”, storia di una trasformazione tra Messico e passione

“Emilia Perez”, storia di una trasformazione tra Messico e passione  Conclave. Ogni papa è eletto da cardinali, ovvero uomini

Conclave. Ogni papa è eletto da cardinali, ovvero uomini  Flow. Dalla Lettonia un lungometraggio animato riscalda il cuore

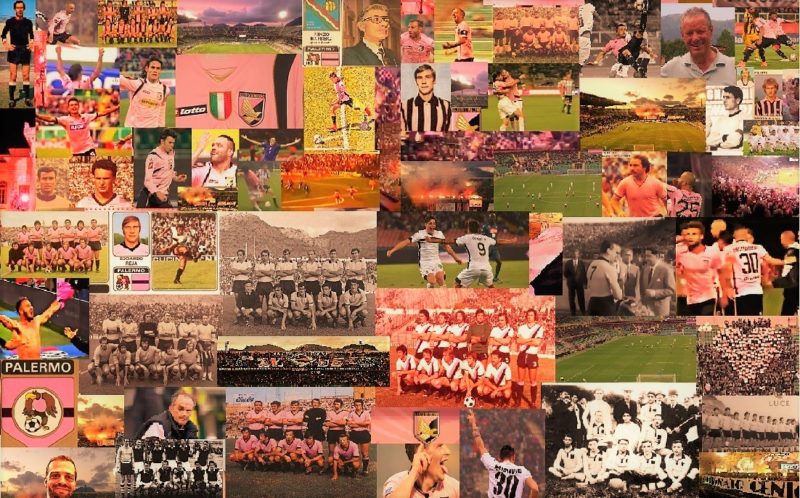

Flow. Dalla Lettonia un lungometraggio animato riscalda il cuore  Compleanno del Palermo. Quando allo stadio c’era la gazzosa

Compleanno del Palermo. Quando allo stadio c’era la gazzosa  “Finalement”, in definitiva capiamo vivendo

“Finalement”, in definitiva capiamo vivendo  “Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra”: il Napoleone della Musica trionfa a Palermo

“Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra”: il Napoleone della Musica trionfa a Palermo