by Gabriele Bonafede

In a nearly 50-pages Monetary Policy Report for May 2021 (here), the Bank of England (BoE) mentions the word “Brexit” just once, at page 21 (page 26 on a pdf viewer). Much of the report ponders on current situation, monetary policy and economic and financial forecast, on a vast array of indicators and economic fields, including business environment and labor market.

Surprisingly, the Bank of England fails to consider Brexit, even in the chapter dedicated to trade. Yet, Brexit is the major economic shock currently ongoing, together with Covid pandemic. Covid is mentioned almost continuously. Brexit is almost entirely forgotten, even for the most affected issues such as, in fact, trade.

Brexit gets mentioned only for what concerns the investment environment and related uncertainty.

“Uncertainty – associated with Covid and Brexit – has weighed on investment in recent years. Most respondents to the DMP Survey suggest that uncertainty remains elevated. And those businesses that report higher uncertainty – or that expect Covid uncertainty to take longer to resolve – also report weaker investment intentions. Uncertainty is expected to decline in the near term; the proportion of respondents citing Covid as their main source of uncertainty fell in the latest DMP Survey.”

Even in this unique occurrence, the word “Brexit” is associated with the word “Covid”. There is no tentative to isolate the two external shocks despite a clear need to ascertain the role of each of them on current crisis.

Reporting Brexit’s impact on trade? Forget about

Right after the above paragraph on investment environment, the report considers trade, with a brief paragraph-title reading “Trade with the EU fell sharply at the start of the year.”

“At the time of the February Report, Agency contacts and high-frequency indicators suggested that UK-EU trade had fallen in January following the move to new trading arrangements. The official trade data have borne that out: UK goods exports to the EU – excluding volatile components – fell by 46% in January, while goods imports from the EU fell by 30% (Chart 2.17).”

Any suggestion on why this plunge in trade, especially export and especially with EU, is occurring? Of course, that is Brexit, as the steep fall in exports due to Covid in spring 2020 is less steep than in early 2021. Yet, the Bank of England fails to mention Brexit even here.

In subsequent paragraphs, the Bank of England mentions Brexit indirectly, ostensibly showing commitment in avoiding that “B” word. And it does so, by minimizing a historic plunge in trade. Yet, the plunge in export is almost entirely to be blamed on Brexit – and it does not seem to be temporary as BoE claims instead.

“Early evidence suggests that firms are beginning to adjust to the new UK-EU trading arrangements. EU goods exports recovered somewhat in February, for example, and were at similar levels to non-EU exports relative to their 2019 averages, although imports from the EU remained very low”, Bank of England reports.

“Recovered somewhat in February, for example”. For example, of what? An example that firms are recovering? Is it a representative example? Arguably, it is not.

No more explanations from Bank of England on trade plunge

No further analysis on trade and trade forecast is reported. It is hard to believe that the Bank of England does not know that Brexit is – at least in part – responsible for the plunge in trade, both for exports and imports, especially with EU. It turns-out that many other institutions are aware of it and publish about it (for ecample here).

And Bank of England cannot be unaware that Brexit’s impact on trade cannot be considered as a short-term temporary effect, as it has – by definition – a persistent effect on trade with the largest pre-Brexit partner – the European Union – hardly replaceable with other partners.

The Bank of England cannot be unaware, either, that trade has a lot to do with currency, monetary policy and inflation targets – the very core of any Central Banks’ business.

In addition, in its statement on trade data, the Bank of England contradicts its own chart (pictured). In fact, the early-2021 plunge in exports to EU is steeper than that registered for Covid in the first half of 2020. That is, when Covid was impacting UK economy while Brexit was not yet impacting it.

And that is visible on the very graphs published by Bank of England itself. Yet, the Bank of England fails to mention Brexit, once again.

A few words in the report are in plain contradiction with what report’s charts say themselves with a thousand words for what concerns exports.

Independence of Bank of England and communication

Is Bank of England still independent? Or is it now aligned to UK’s government political necessities? This May-2021 report suggests both questions maybe relevant. Especially when considering the current social and political phase in the UK.

The Bank of England is proud of its independence. It states loudly its commitment to independence on its official web page.

“For over 250 years, until it was nationalised in 1946, we were a private bank owned by various shareholders. Today, we are owned by the UK Government, who appoint all of our senior policymakers. But we have independence from the Government in terms of how we carry out our responsibilities. What does this mean? Well first of all, Parliament has given us very precise goals and responsibilities. For each one, we have specific tools we can use to meet our objectives.”

Independence of central banks is a prerequisite for good monetary policy, no doubt about that. Should independence be extended to Central bank’s communication too? Probably, yes. As communication is determinant for the success of any central bank’s action.

Yet, the May 2021 report from Bank of England seems to accommodate a word too many with UK government’s communication mode – and not only on avoiding as much as possible the “B” word.

We all know that Brexit has been currently banned from political speeches, especially for what concerns politicians supporting the current government. It is not acceptable that British press is seldom mentioning Brexit precisely when its impact is proving strong on all fields of UK’s life.

It is less acceptable that the Bank of England avoids using it in a report that – in addition – shows acquiescence with UK government’s economic policy, in turn essentially based on Brexit itself.

Ignoring a storm does not make that storm easier

It is a pity to see such a situation. All the more, when we know that a few months ago the governor of Bank of England had been pointing out that Brexit could cost more than Covid. As reported (here) by the Guardian as recently as November 2020: ‘No-deal Brexit to cost more than Covid, Bank of England governor says’.

True, since January 2021 there is a deal. But it is a hard-Brexit deal, already proving to be not so far from an unsustainable no-deal.

Brexit in itself, and especially the Current Brexit deal, is an economic, political and institutional storm for UK. Ignoring a storm does not make that storm easier.

On cover, photo by Nikolas Noonan on Unsplash. On text, photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash and photo by NASA on Unsplash

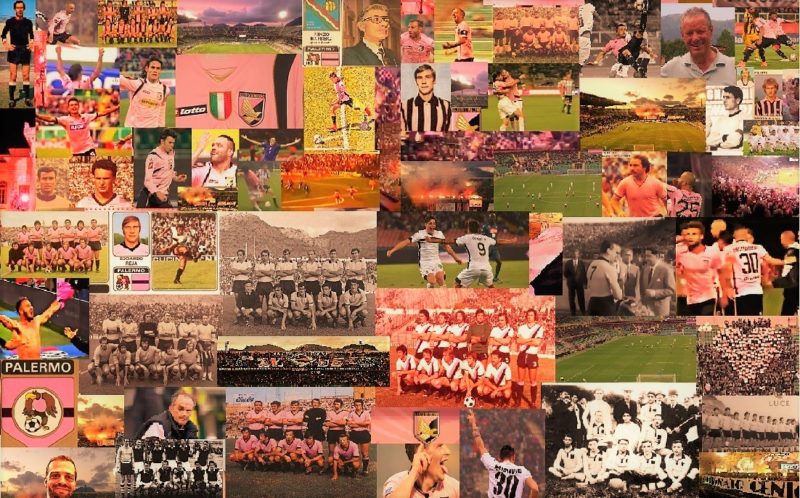

Compleanno del Palermo. Quando allo stadio c’era la gazzosa

Compleanno del Palermo. Quando allo stadio c’era la gazzosa  “Finalement”, in definitiva capiamo vivendo

“Finalement”, in definitiva capiamo vivendo  “Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra”: il Napoleone della Musica trionfa a Palermo

“Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra”: il Napoleone della Musica trionfa a Palermo  “It ends with us”, quando cambiare non è facile, per nessuno

“It ends with us”, quando cambiare non è facile, per nessuno  “Il Derviscio di Bukhara”: la magia e il fascino dell’Oriente

“Il Derviscio di Bukhara”: la magia e il fascino dell’Oriente  Kursk, continua l’offensiva ucraina. Amministrazione russa nel caos

Kursk, continua l’offensiva ucraina. Amministrazione russa nel caos