(In questo link la versione originale in italiano)

by Pasquale Hamel

Lord William Cavendish-Bentinck reached Sicily in the summer of 1811. At that time, the island is practically under British control and had been militarized to prevent French troops, masters of almost all of Europe, from occupying it.

In Sicily, Lord Bentinck, holds a double office. In fact, he is the diplomatic representative accredited to the Bourbon court but he is also the commander of the forces of His Majesty King George stationed on the island.

He is a man of great experience and a staunch supporter of the constitutional system of Great Britain. That leads him to develop feelings of aversion towards the Bourbon monarchy whom he considers despotic and obscurantist – and very ambiguous in behavior.

William Bentinck and the Bourbons of Naples

He shows a particular hostility towards Queen Maria Carolina of Austria, wife of Ferdinand, Bourbon king of Naples and Sicily. Bentinck considers Maria Carolina too intriguing and unreliable. His arrival happens in the middle of a conflict between the Sicilian nobility, gathered in Parliament, against the Napolitan king. The subject of conflict is the request for an increase in the tax burden that the Sicilian Parliament, which is responsible for the decision, rejects.

The response of the Bourbons is authoritarian. Queen Maria Carolina, whose influence is very strong, orders the arrest and deportation of the opposition leaders to small islands around Sicily, provided with military castles used as hard prisons.

On July 19, 1811, the princes Giovanni Ventimiglia of Belmonte and Carlo Cottone of Castelnuovo are deported to the prison of Favignana island. The prince Alliata of Villafranca is confined to the island of Pantelleria, the prince Giuseppe Reggio d’Aci to Ustica and the Duke of Anjou to Marettimo.

Bentinck, despite having recently arrived and therefore poorly informed about the facts, decides to intervene. He asks to be received by King Ferdinand. With the authoritarian air of a true master of Sicily, William Bentinck urges the revocation of the restrictive measures.

King Ferdinand is unable to reject the request of the English plenipotentiary and, after some useless prevarication, orders the release of the five rebels. But Bentinck goes even further and continues meddling in the affairs of the Sicilian government.

He supports the initiative of Sicilian barons who oppose royal absolutism and aspire to obtain a constitutional charter.

The Sicilian constitution of 1812

The model to which Bentinck addresses them is the English one. Abbot Paolo Balsamo, an expert jurist, draws up the text. Parliament is therefore summoned against the will of King Ferdinand. Not wanting to sign the constitutional charter, on January 16, 1812 the King self-suspends himself, transferring royal functions to his son Francesco. Prince Francesco is therefore appointed a “vicar general”, and assigned the powers of the father.

The constitutional charter is drawn up under the watchful eye of Lord Bentinck during 1812 and published on May 25, 1813. That Charter, known as the Sicilian Constitution of 1812, bears the signature of the heir to the throne Francis (Francesco) of Bourbon and not of King Ferdinand. Meanwhile, the contrasts between Bentinck and the Bourbon court are gradually becoming stronger.

It is no coincidence that Bentinck imposes the removal of Maria Carolina from Palermo. Strengthened by the fact that the English troops are the only support to the Kingdom f Sicily – and that they make a substantial contribution to the island’s economy – he dictates the political agenda.

Bentinck’s support for the annexation of Sicily to Great Britain

It is at that time that his idea of expelling the Bourbon dynasty and associating the island with the possessions of His British Majesty matures. It is an ambitious project which, however, does not find the consensus in London. Despite having full control of Sicily, the Britsh government does not want a confrontation with Austria before defeating Napoleon.

Meanwhile, events precipitate. The Napoleonic thrust is going to run out. After having subdued much of Europe by overthrowing ancient monarchies and insinuating a wave of novelty that marked the end of the so-called ancièn regime, Napoleaon experiences militar defeats.

In Leipzig, at the Battle of the Nations of 1813, Napoleon is defeated by his enemies and so they prepare to return as rulers. William Bentinck, at this point, meditates to take advantage of the situation to raise Italians against France and extend the constitutionalism experienced in Sicily. He hopes to help consitutionalism throughout the Italian peninsula.

In command of his troops, he targets Milan. But, having reached Genoa, he must acknowledge that the Austrian forces preceded him, thus dashing his ambitious project. His return to Sicily is a sort of certification that his project has essentially failed and the forces of conservation had won. The Bourbons had managed, thanks to the support of the Austrians, to regain the lost positions.

Bentinck’s Sicilian adventure ends with a melancholy return to his homeland where his battle against conservative forces continues. Then he will return, as governor, to India. But this is another story.

On cover (cut) e nel testo (original), Lord William Cavendish-Bentinck. Par http://www.jochen-moeller.de/grafik_galerie/admin/bestellen.php/art/1356, Domaine public, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1979375

Translation from Italian and editing by Gabriele Bonafede.

Related articles:

Sicily and Britain. A history of common European heritage

St Patrick’s Day 2021, Ireland and the Unification of Italy

“Emilia Perez”, storia di una trasformazione tra Messico e passione

“Emilia Perez”, storia di una trasformazione tra Messico e passione  Conclave. Ogni papa è eletto da cardinali, ovvero uomini

Conclave. Ogni papa è eletto da cardinali, ovvero uomini  Flow. Dalla Lettonia un lungometraggio animato riscalda il cuore

Flow. Dalla Lettonia un lungometraggio animato riscalda il cuore  “Finalement”, in definitiva capiamo vivendo

“Finalement”, in definitiva capiamo vivendo  “Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra”: il Napoleone della Musica trionfa a Palermo

“Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra”: il Napoleone della Musica trionfa a Palermo  “It ends with us”, quando cambiare non è facile, per nessuno

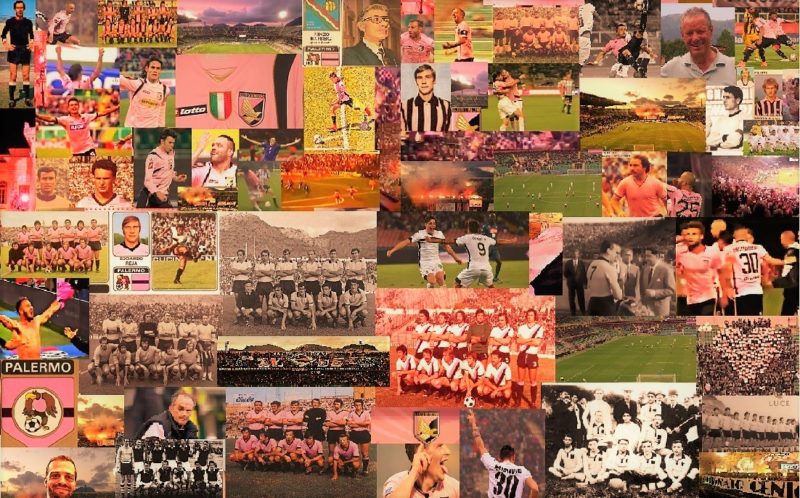

“It ends with us”, quando cambiare non è facile, per nessuno  Compleanno del Palermo. Quando allo stadio c’era la gazzosa

Compleanno del Palermo. Quando allo stadio c’era la gazzosa